31 December 2025

bonus track

Yitian Xu.

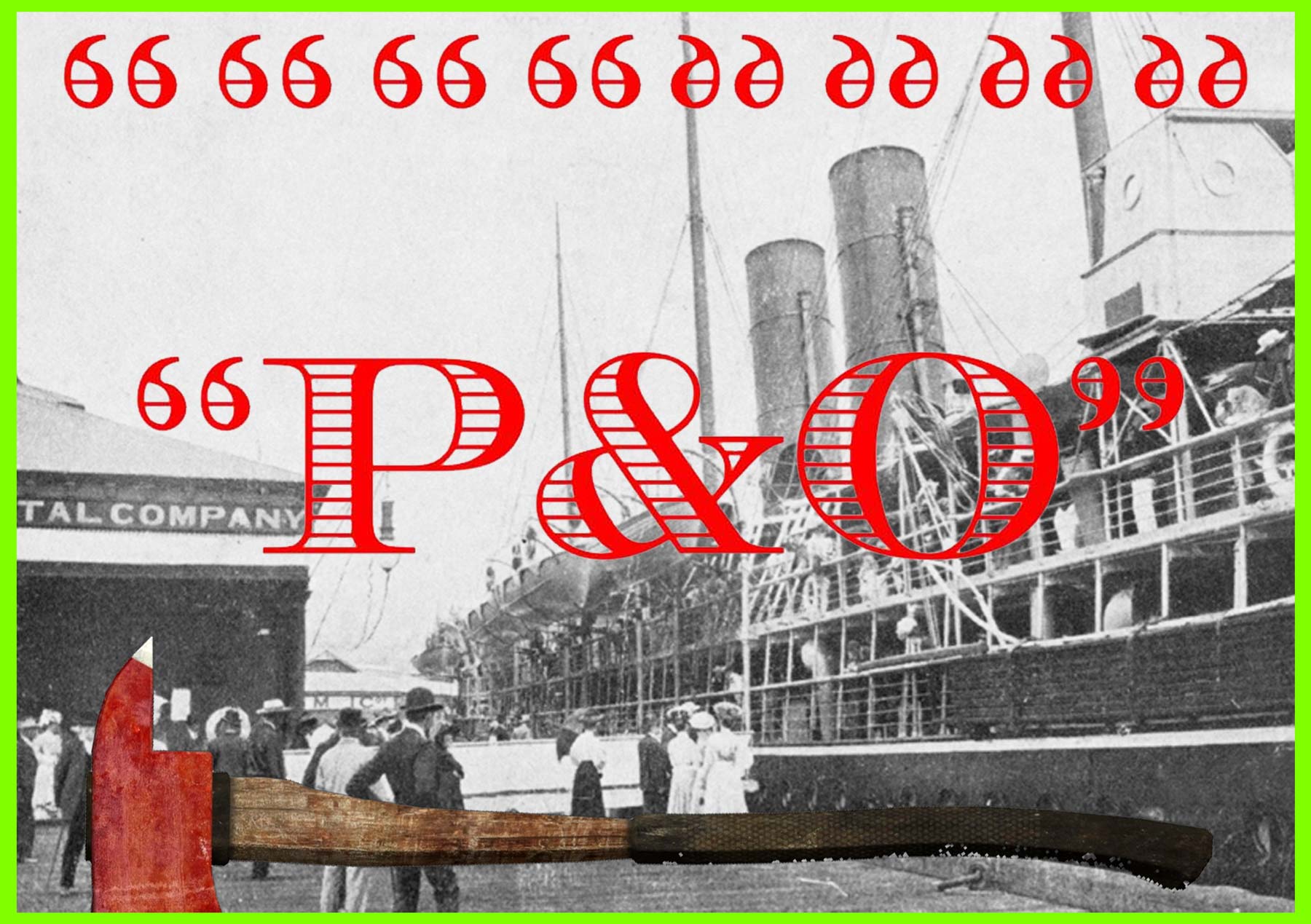

P.&O., 1925.12.31

Radio Play – 9’7’’2025

photo (c) Yitian Xu

Synopsis: A sonic excavation of the Imperial

route between London and Singapore on New Year's Eve, constructed through a

superimposition of timelines (1925/2025) and voices.

Text

P&O Narrative & The Debris. Original script, 2025.

The Imperial Route (Chinese). Original script, 2025.

Travel Diary (Excerpts). Original script, 2025.

Maugham, W. Somerset. P.&O., 1926.

Sound

Li Ge (骊歌)[Chinese Adaptation].

You Yi Di Jiu Tian Chang (友谊地久天长) [Chinese Adaptation].

Auld Lang Syne [Original Scots / Robert Burns].

Translation of The Imperial Route

Before entering the port, we must first understand the composition of this route's 'cargo.' In 1925, P&O liners transported more than just mail and rubber; they also carried a specific sociological phenomenon known as 'The Fishing Fleet.'

This term referred to single British women traveling in Third Class to the Eastern colonies. In the Far East, where the gender ratio was severely imbalanced, their objective was to find a husband—whether a planter or a colonial official. If they were not engaged by the end of the voyage, they would return the way they came. In the slang of the crew, these failed returnees bore a cruel label: 'Returned Empties.'

When this 'Fishing Fleet' docked, they faced three distinct manifestations of the British Empire.

The first stop: Singapore. Officially defined as the 'Straits Settlements.' Here lies an obscure economic fact unknown to tourists: In 1925, Singapore possessed the cleanest streets in the world, but where did the maintenance funding come from? The answer is: Opium. The Singapore government at the time was a legal drug distributor. In that year, nearly 40% of the colonial government’s revenue was derived directly from selling opium to Chinese coolies. The civilized façade of the British Empire was, in reality, sustained by the money of addicts.

The second stop: Hong Kong. As the P&O liner steamed into Victoria Harbour, passengers would look up toward The Peak. It was the vantage point with the finest views. But they likely did not know of a law called the Peak District Reservation Ordinance. It explicitly stipulated that only Europeans were permitted to live on the Peak. In Hong Kong, physical elevation was directly equated with racial class. Moreover, 1925 was a peculiar year. When P&O docked, the place was effectively a 'dead city.' Due to the outbreak of the Canton-Hong Kong General Strike, the entire city was paralyzed for a full sixteen months. This silence was something far more terrifying than a tropical storm.

The final stop: Shanghai. It was not a colony; it was called the 'International Settlement.' It was a 'state within a state.' Although the streets bore names like 'Nanking Road,' they did not fall under the jurisdiction of the Chinese government. They belonged to the Municipal Council—a wealthy club composed of foreign taxpayers. Thus, when P&O passengers disembarked in Shanghai, even if they committed a crime, the Chinese police could not arrest them. Because, in a legal sense, they had never left the jurisdiction of Great Britain.

And in the sonic backdrop of all this, there was that Scottish ballad: Auld Lang Syne. On New Year's Eve in the colonies, white colonizers would link arms in a circle and sing, affirming their solidarity and their presence.

But when this melody crossed the barbed wire of the settlements and entered Chinese schools, its meaning shifted. In China, the lyrics were adapted into Li Ge (The Farewell Song). Around 1925, this was also the graduation anthem of the Whampoa Military Academy. For the British on the ship, the melody signified 'toasting' and 'continuity'; But for the Chinese officers and students on the shore, the melody signified 'parting' and 'sacrifice'—a tragic solemnity implying that 'once we part, we may never meet alive again.'

It was not until much later that another translation, Friendship Everlasting, would reimbue it with the meaning of reunion. But in 1925, this same melody was a celebration on the ship, and an elegy on the shore.

Yitian Xu.

Writer, game designer, and art theorist.

Text

P&O Narrative & The Debris. Original script, 2025.

The Imperial Route (Chinese). Original script, 2025.

Travel Diary (Excerpts). Original script, 2025.

Maugham, W. Somerset. P.&O., 1926.

Sound

Li Ge (骊歌)[Chinese Adaptation].

You Yi Di Jiu Tian Chang (友谊地久天长) [Chinese Adaptation].

Auld Lang Syne [Original Scots / Robert Burns].

Translation of The Imperial Route

Before entering the port, we must first understand the composition of this route's 'cargo.' In 1925, P&O liners transported more than just mail and rubber; they also carried a specific sociological phenomenon known as 'The Fishing Fleet.'

This term referred to single British women traveling in Third Class to the Eastern colonies. In the Far East, where the gender ratio was severely imbalanced, their objective was to find a husband—whether a planter or a colonial official. If they were not engaged by the end of the voyage, they would return the way they came. In the slang of the crew, these failed returnees bore a cruel label: 'Returned Empties.'

When this 'Fishing Fleet' docked, they faced three distinct manifestations of the British Empire.

The first stop: Singapore. Officially defined as the 'Straits Settlements.' Here lies an obscure economic fact unknown to tourists: In 1925, Singapore possessed the cleanest streets in the world, but where did the maintenance funding come from? The answer is: Opium. The Singapore government at the time was a legal drug distributor. In that year, nearly 40% of the colonial government’s revenue was derived directly from selling opium to Chinese coolies. The civilized façade of the British Empire was, in reality, sustained by the money of addicts.

The second stop: Hong Kong. As the P&O liner steamed into Victoria Harbour, passengers would look up toward The Peak. It was the vantage point with the finest views. But they likely did not know of a law called the Peak District Reservation Ordinance. It explicitly stipulated that only Europeans were permitted to live on the Peak. In Hong Kong, physical elevation was directly equated with racial class. Moreover, 1925 was a peculiar year. When P&O docked, the place was effectively a 'dead city.' Due to the outbreak of the Canton-Hong Kong General Strike, the entire city was paralyzed for a full sixteen months. This silence was something far more terrifying than a tropical storm.

The final stop: Shanghai. It was not a colony; it was called the 'International Settlement.' It was a 'state within a state.' Although the streets bore names like 'Nanking Road,' they did not fall under the jurisdiction of the Chinese government. They belonged to the Municipal Council—a wealthy club composed of foreign taxpayers. Thus, when P&O passengers disembarked in Shanghai, even if they committed a crime, the Chinese police could not arrest them. Because, in a legal sense, they had never left the jurisdiction of Great Britain.

And in the sonic backdrop of all this, there was that Scottish ballad: Auld Lang Syne. On New Year's Eve in the colonies, white colonizers would link arms in a circle and sing, affirming their solidarity and their presence.

But when this melody crossed the barbed wire of the settlements and entered Chinese schools, its meaning shifted. In China, the lyrics were adapted into Li Ge (The Farewell Song). Around 1925, this was also the graduation anthem of the Whampoa Military Academy. For the British on the ship, the melody signified 'toasting' and 'continuity'; But for the Chinese officers and students on the shore, the melody signified 'parting' and 'sacrifice'—a tragic solemnity implying that 'once we part, we may never meet alive again.'

It was not until much later that another translation, Friendship Everlasting, would reimbue it with the meaning of reunion. But in 1925, this same melody was a celebration on the ship, and an elegy on the shore.

Yitian Xu.

Writer, game designer, and art theorist.

homepage